Schroeder stairs illusion: how our brain transforms 2D retinal projections into 3D reality

- Physics Core

- Nov 23, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 24, 2025

The Schroeder stairs illusion (Fig. 1) is a classic example of perspective reversal, often used in research on how our brain interprets reality. The drawing is stripped of the cues indicating its spatial orientation. In the absence of these cues, the brain struggles to produce a clear 3D interpretation of this 2D structure, switching between two equally plausible, yet mutually exclusive perspectives. In the first scenario, the stairs appear to be viewed from above (Fig. 1, left image), with panel A in the foreground and steps rising from right to left. In the second scenario, the same pattern is perceived as the stairs seen from below, with panel A in the background and steps rising from left to right (Fig. 1, right image).

The illusion was named after the German natural scientist Heinrich G. F. Schröder, who published it in 1858. Not everyone can easily switch between the two viewpoints, as it depends on how adaptable your brain is in accepting ambiguous solutions. When faced with an image that allows for multiple 3D interpretations, the brain may choose a preferred option based on past experiences. This preferred assumption becomes dominant, making it hard for the brain to disengage from it and adopt an alternative view. In Fig. 1, the pattern is rotated 90 degrees to assist you in visualising both perspectives. However, it is essential to experience the flip in action to understand how our brain generates 3D solutions. If your brain stubbornly resists switching modes, you can try the following exercise.

In Fig. 2, the central image shows the staircase at the halfway point of a 90° rotation. This intermediate position allows for effective engagement with both perspectives shown on the left and right. Cover the left image with your hand and shift your focus between the letter B in the center and the right image to bring Panel B forward. When this is achieved, the brain will reverse direction, and you will see the steps appear to ascend from left to right in the central image. To return to the previous mode, cover the right image and shift your focus between the letter A in the left and central images. This will bring Panel A forward, causing an illusion that the steps ascend from right to left.

If needed, you can tilt your head or lie down to relax your eyes. Once the dominant pattern is disrupted, the perceptual reversal is triggered, allowing the central image to change orientation freely. Perceptual flexibility is generally greater in children and gradually decreases as we reach adulthood. Younger brains are still building internal models of the world, so they are more open to accepting ambiguous outcomes. As we get older, the brain becomes less adventurous and more reliant on established pathways, tending to settle on a single option and stick with it.

The impression of viewing the stairs from above or below is due to how the treads and risers are projected onto the retina. When observing the stairs from above (Fig. 3, left), the horizontal treads are more visible, while the vertical risers appear hidden. The brain interprets the pattern of wider treads and narrower risers as consistent with the elevated position of the viewer. In contrast, when we stand at the bottom of the stairs (Fig. 3, right), we face the vertical risers, which makes them appear wider and the treads compressed. The brain interprets this shift in proportions as a cue that the viewer is positioned at the bottom of the stairs.

In Fig. 1, the lighter bands are wider than the darker ones. This difference provides visual cues about the observer's position relative to the stairs. The first interpretation brings Panel A forward, making the light bands appear horizontal. The horizontal bands are always treads, as they are the only parts that can support the climber's weight. Since they are wider than the risers, the stairs must be viewed from above. The second interpretation brings Panel B forward, turning the treads into risers. Now, with the risers appearing wider, the apparent viewpoint shifts from above to below.

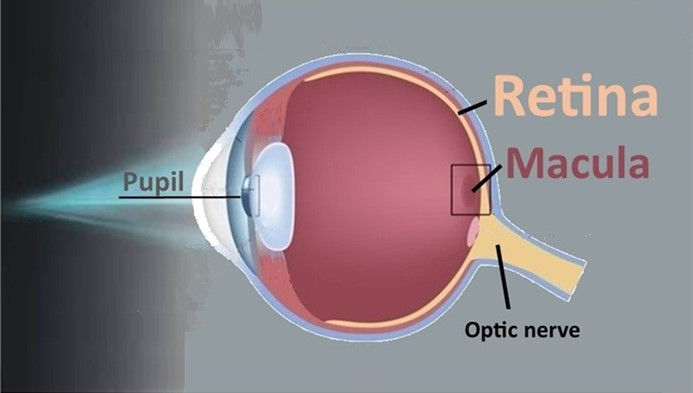

Information about the world is delivered to us by light that activates photoreceptors in the retina, located at the back of the eyeball (Fig. 4). As a curved, two-dimensional sheet of cells, the retina can only record two-dimensional projections of our three-dimensional environment. Thus, every scene we view is encoded as a flat pattern of light wavelengths and intensities. From this inherently incomplete information, the brain must reconstruct a coherent 3D interpretation of the objects and their spatial relationships. This reconstruction relies on the contextual cues, some examples of which we have examined using Schroeder's illusion.

We see the world in a flat mode. A third dimension, depth, is created by our brain using cues stored in our memory. This mechanism may not be perfect, but it allows us to navigate our surroundings with remarkable accuracy. Essentially, the reality as we perceive it is a sequence of 2D “snapshots” captured by the retina, which our brain converts into a stream of unfolding 3D events. Space has no inherent directions, such as left and right, up and down, or front and back; these orientations exist only in relation to an observer. When cues are muted, the brain either experiences a perceptual flip or selects the dominant interpretation that has been prioritized through past life experiences.

Comments